Hello and Happy New Year! I’ve been meaning to return to my Method Books theme for over a month now, and finally can after a busy December touring with Christmas Celtic Sojourn up in Boston. Here I’ll cover the Clarinet Method of Benny Goodman, along with the Saxophone Method of Jimmy Dorsey. Two Swing Era stars, their books are in very similar formats.

Benny Goodman’s Clarinet Method

I was first drawn to the Benny Goodman book after reading that Paul Desmond was practicing out of it in the 40’s, when he was still a clarinetist primarily. He also mentions the Baermann book, a favorite of mine and one that I’m practicing out of quite a bit currently.

Goodman stays pretty standard for the first half of the book, long tones, dynamic range exercises, scales in all keys and intervals followed by some diatonic tunes for phrasing. He then includes a bunch of 2 measure repetitive fingering exercises, similar to the Baermann, which are great for working out technical issues and going into a Phillip Glass-esque trance at the same time.

It gets interesting towards the end. The last few pages before the transcriptions are what he calls “Modern Studies in Rhythm” The rhythms are mostly 8th notes in bizarre chromatic motion. A lot of not-quite patterns abound and nothing implies a very clear chord structure. I’m not sure if these are meant to be Modern, as in jazz, or Modern, as in 20th Century Classical music. Also unclear is whether these exercises should be swung, as in the Artie Shaw and Jimmy Dorsey books. Here’s a recording I made of one of them, it made a little more sense to me.

There’s not much else to this one, no words of wisdom, some full band transcriptions towards the end of some of Benny’s biggest hits.

Jimmy Dorsey’s Saxophone Method

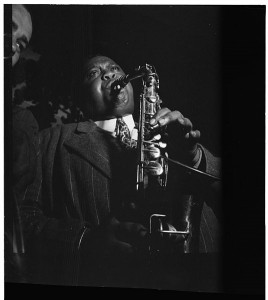

Jimmy Dorsey was a great big band leader, who broke off from his brother Tommy Dorsey, and moved out to Hollywood, where his band would appear in films. Like this one:

He has a clarinet-like sound and approach, which you can hear above. There are some nice things in this book: an exhaustive amount of scales, tonguing exercises, and arpeggios along with some nice little pieces aimed at learning legato swing tonguing. Then he goes into the usual etudes for learning syncopation and new time signatures, similar to the Goodman book, but the melodies are of the more cute variety.

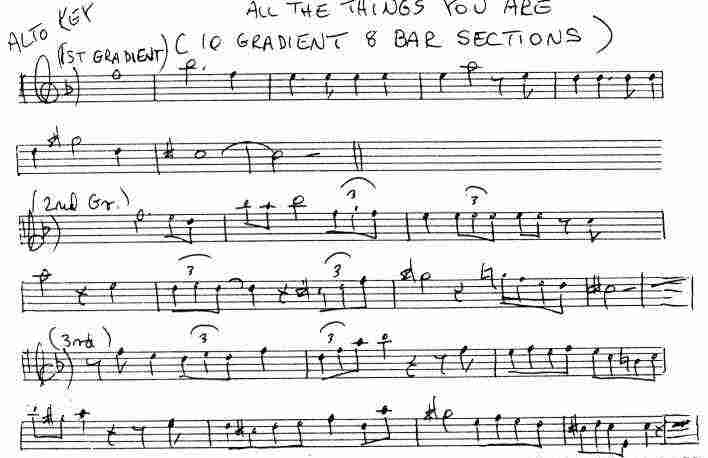

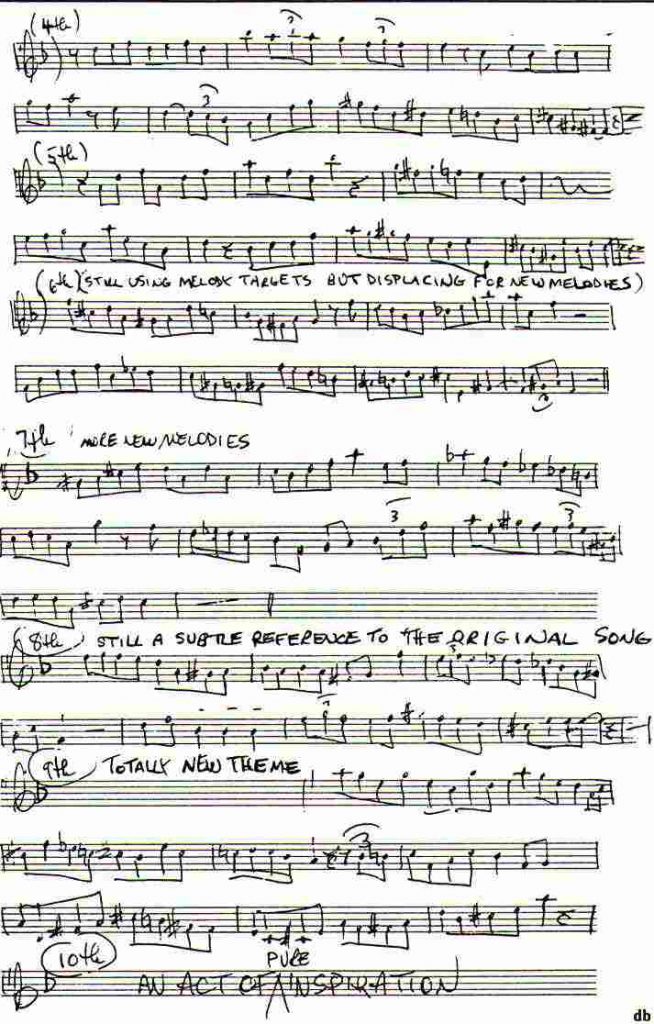

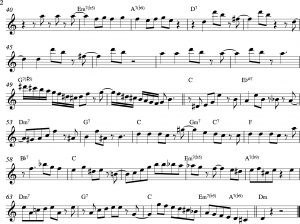

What’s really interesting is the second half of the book, which explains the various types of dance music, and how to start to improvise through chord progressions. This has to be one of the first books to discuss that. He talks about the Foxtrot, Tango, Rumba etc., explains chord structure, then gives a bunch of sample chord progressions to be studied. This is followed by phrases on different chords, following the line where he says, “the notes which may be used to form the melodic line of your improvisation are the notes forming the chord plus embellishing notes.” The licks are nothing too exciting, but a good insight into early swing big band vocabulary. Finally there are transcriptions, including this tune, Tailspin, where Dorsey takes a couple of burning solo breaks!

Both of these books are still in print, and while they may not break any new ground for the modern woodwind practitioner, I still think they are worth having in the library.